SLASHER MOVIE SCORES - TEN SCORES TO REMEMBER

The slasher movie sub-genre didn’t arrive with a roar; it crept in on a whisper. Bob Clark’s "Black Christmas" (1974) laid the groundwork—intimate spaces violated, the killer’s-eye gaze, victims isolated and helpless towards a killer force so menacing that becomes unbeatable. The movie wasn’t a hit machine, but it defined the characteristics of a new form. Four years later, John Carpenter’s "Halloween" (1978) refined that language into pop mythology. An ordinary suburb rendered uncanny, a mask without a face, and a score of icily repeating figures that became the definitive sound of cinematic horror for a new era.

The 1980s turned the new sub-genre

into an industry. "Friday the

13th" (1980) commercialized the formula—summer camp, campfire

guilt, practical-gore punctuation—and Harry Manfredini’s whispered “ki-ki-ki,

ma-ma-ma” entered the cultural bloodstream not by following the steps of the ultra-successful

John Carpenter synthetic music, but reworking the sound Bernard Herrmann

created for "Psycho". The movie established the new style by introducing one

more iconic menacing figure, and the formula was now full. The almost

superhuman killer, the set-piece murders, the naïve youngsters-victims, the

ominous distressing music.

Soon after, "A Nightmare on Elm Street" (1984) introduced a villain who talked back. Suddenly the boogeyman had a personality and an origin myth. The slasher movie entered the supernatural territory with a bang! Between those poles—stoic shape and motor-mouthed monster—the sub-genre exploded: regional productions, direct-to-video upstarts, and studio sequels, each promising new ways to stalk, misdirect, and deliver the kill.

Alongside the images, the sound of the slasher

solidified. John Carpenter’s metronomic synths set the mood. Minimal,

relentless, cheap enough to replicate, abstract enough to haunt. In their wake

came nervy strings and drum machines, library cues hacked into menace, and

those unmistakable textures—breathy pads, stabbing clusters, music-box motifs

turned sour. From Manfredini’s jagged crescendos to Pino Donaggio’s lush

perversity, from Jay Chattaway’s urban chill to Charles Bernstein’s keyboard

nightmares, the scores did more than decorate; they taught audiences how to

feel fear in four notes and a pulse.

The following article doesn’t

re-litigate the canon so much as shine a light on the other gems, leaving out of the

party the Halloween, Friday and Elm Street movies. These movies are so celebrated

that even my 95 year old neighbour is more or less aware of their legacy.

Below, you will read about ten

movies and their scores that are among the most important of the slasher sub-genre,

each for a different reason. You will read about seasonal massacres and

sorority terrors, alleyway psychosis and carnivals that smell like rust. We’ll

track how these titles fit into the boom, what they borrowed, what they

invented, and how their music wired dread directly into the nervous system.

BLACK CHRISTMAS (1974)

Four years before the big bang of John Carpenter’s «Halloween», director Bob Clark made a great sensation with two superb horror movies both released in the same year (1974). The first was «Dead of Night» (aka Death dream)– a nightmarish comment on the tragic consequences of the Vietnam war to the average American family – and the second was «Black Christmas», the worst nightmare of the upper-middle class complacency. A violent, blood-soaked invasion into the nostalgic, cozy stronghold of the Christmas Holidays. As if that were not enough, it plays out in a sorority house in a fictional, ice-bound Canadian town. The film is built upon the nasty-simple idea of an unseen killer already inside a sorority house filmed with voyeuristic POV shots, obscene phone calls, and an ending that refuses to tidy up. Those choices quietly set the template later films would polish, especially the killer’s-eye perspective and the “safe space turned hunt ground” vibe that «Halloween» would mainstream a few years later. Clark and John Carpenter even discussed sequels and influence back then, and most retrospectives now credit «Black Christmas» as a key stepping stone to «Halloween»’s breakthrough.

What seals the

film’s mood is Carl Zittrer’s score. Not hummable themes, but a

nerve-scraping sound design consisted of prepared/detuned pianos, manipulated

concrete sounds, distorted Christmas songs, breaths and voices smeared into

dissonance. It feels less like traditional music score than the soundtrack of a

Christmas nightmare. In my opinion, Black Christmas would have been another

movie with a traditional orchestral music score. The way Bob Clark utilized

sounds in order to create the right mood for his movie was innovative and

brave, in the vein of William Friedkin’s Exorcist score, where dissonancy and

cacophony became a crucial tool in the hands of the director in order to

enhance the shock factor.

For decades the

score masters never had a proper release since nobody dared to release such a

blasphemous and obscene soundtrack. The masters were considered lost until they

were tracked down for an archival issue by Waxwork Records in 2016 and in 2022.

ALICE SWEET ALICE (1976)

«Alice Sweet Alice» is one of those grubby little 70s horror films that feels like you shouldn’t be watching it, and that’s basically the point. Set in a Catholic community and circling around a young girl who may or may not be a killer, the movie leans into guilt, religious paranoia, and sleaze. It’s best known now for having a very young Brooke Shields in an early role, but the real personality of the film comes from how mean and uncomfortable it is. It’s cheap, angry, and mostly a bridge between Italian giallo and the American slasher sub-genre that appeared a few years later.

Stephen Laurence’s score leans

into that sickly, off-kilter mood with its creepy structure using

children’s-melody vibes, tense strings, imposing a sense of rot under

innocence. Much different than the electronic sounds John Carpenter imported to

the genre a couple of years later, much different than the Italian giallo sound

of Morricone, Nicolai and Cipriani, Lawrence’s score is an orchestral score

that is focused in creating an uneasy atmosphere through dissonant strings and

repetitive piano figures, even utilizing a church-organ to build the dark,

ominous atmosphere of the film’s final moments. The score lacks melodic

elements and It’s not a surprise that nobody in 1976 was lining up to release it

on record.

It was Waxwork Records that

produced a superb edition 25 years later, both on vinyl and cd. The LP came on

heavyweight 180-gram vinyl in two different color variants in yellow vinyl, direct

nod to that sinister little rain slicker from the film — and it was packed in

an old-style tip-on gatefold sleeve with brand new artwork by Steven Reeves.

There’s also a thick insert, original 1976 session photos, and liner notes from

the composer himself. The label also issued it on CD which surprisingly is

scarcer than the LP editions.

TOURIST TRAP

(1979)

Imagine a version of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, with a parodic albeit dark direction, with a dragging pace and a dreamy style and you have «Tourist Trap», a nightmare roadside attraction stretched to feature length, all mannequins, echoey reverb voices, and sticky sweat. The movie defines David Schmoeller’s deal as a director, atmosphere first, logic second. Check his later career and you’ll get the point. A maniac with telekinetic powers terrorizes a bunch of youngsters with his terrifying dolls and kills everyone around. Telekinetic doll scenes are genuinely uncomfortable and uncanny, Chuck Connors is perfectly fitted into the role of the maniac with telekinetic powers and Pino Donaggio’s score is one of the most unusual and controversial of his entire career, and certainly a curiosity in horror movie film music.

Donaggio doesn’t follow predictable and

cliché slasher movie methods. Instead of sharp stings and shock hits the score

goes dreamy or «nightmarish» if you prefer better. You get these delicate,

almost childlike melodies, music box, lullaby vibes and creepy voices, floating

over scenes that are violent and ugly. Donaggio knows how to use violins and he

utilizes a large string orchestra in a way reminiscent of his De Palma works,

but the overall feeling of the score is utterly unique and innovative for a

genre movie.

It was Varese Sarabande label,

which back in the beginning of 80s was building its legend with releases of

horror movie soundtracks, that released an LP with Donaggio’s full score. A

record that after the second coming of vinyl in the mid-2010s saw its price

escalate to three-digit numbers. Waxwork Records re-released the album in 2015.

MANIAC (1980)

William Lustig’s «Maniac» is one of the ugliest, sweatiest slashers ever made, and that’s exactly why it matters. Where a lot of early ’80s slashers were basically carnival rides, Maniac is just pure filth and sickness. It doesn’t try to be fun. It drags you into the head of a killer and doesn’t let you back out. Stylistically, it’s street grime. The movie is shot in real New York at the time, when the city still looked dangerous just by existing. There’s no glossy lighting, no cute one-liners, you get Joe Spinell as a sad, sweaty, heavy-breathing creep with mommy issues and not some masked boogeyman with mythology. This makes the violence more nasty and personal. Tom Savini’s practical gore effects are still notorious — not because they’re gory, but because they feel mean. The camera doesn’t cut away politely. It lingers. And that lingering was a big deal. It pushed how far slashers could go in showing the kill instead of implying it. «Maniac» was the turning point of the slasher film from campfire story into psychological rot. After «Halloween» (1978), the slasher villain felt almost mythic: The Shape, the mask, the rules. After «Maniac», you had this other lane where the killer was human, filthy, mentally broken, and the movie forced you to sit in his point of view. The influence in genre cinema was huge and the “inside the killer’s head” angle was never shown like this before in cinema.

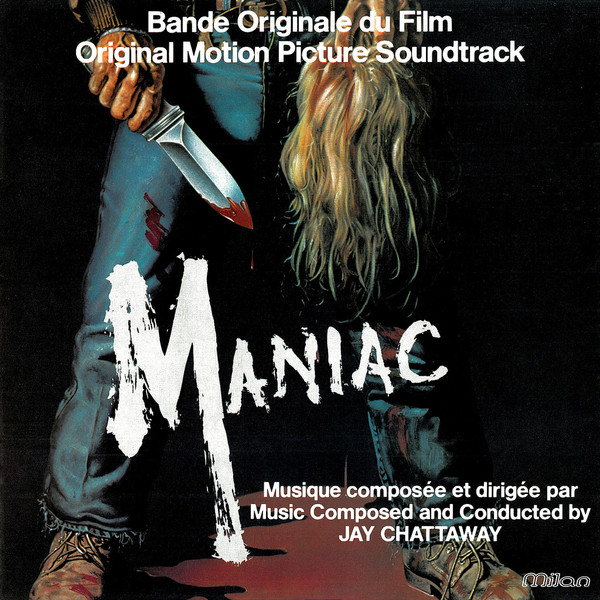

Jay Chattaway’s score for «Maniac»

is a very well-balanced study in character and horror. Contrary to «Friday

the 13th » score that same year, he doesn’t go orchestral,

instead he builds tension with cold synth pulses, low bass drones, and sudden

percussive snaps that feel mechanical and impersonal, like the killer’s nervous

system ticking. The score is built around a sad tune for the central character,

that is used mostly to remind to us that Frank Zitto is more than a killing

machine, however while the flute interpretation focuses on the tragic backstory

the bass glissandos transform it into an ominous precursor of his nightmarish

nature. You can hear clear influences of John Carpenter’s «Halloween» score,

but Chattaway finds the way through his superb main motif and atmosphere to

create one of the most memorable genre scores.

The original album releases by

Varese Sarabande, Milan and Cinevox are notorious for their collectible value.

Especially the Varese issue with its striking cover (Milan also utilizes the

same cover), has escalated in value to amounts that surpass the 150$ barrier.

Mondo records reissues have somehow covered the high collector’s demand and

also reached super high prices but haven’t got the collectability and value of

the originals.

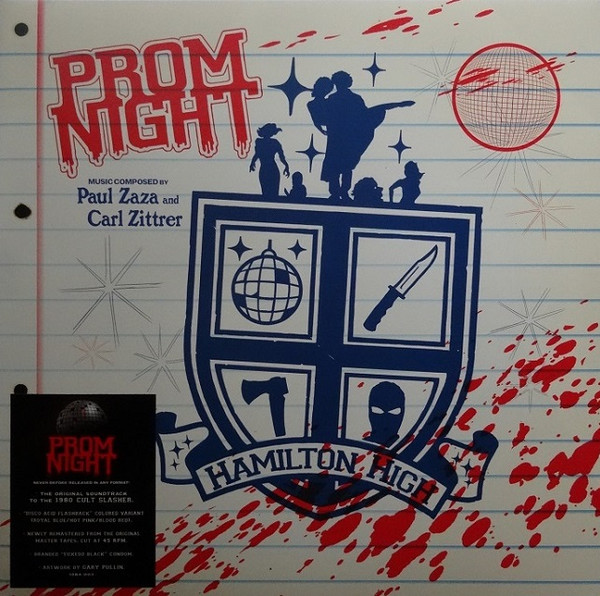

PROM NIGHT (1981)

«Prom Night» is perhaps the only existing slasher horror that the main killer’s action is accompanied by disco music! Actually, Paul Zaza and Carl Zittrer split «Prom Night»’s musical personality right down the mirror ball. Halfway through the movie we have the title’s prom night begin and that’s where Paul Zaza takes the control and fizzy, relentless disco pastiches pumping through the speakers while Jamie Lee Curtis spins under the lights. This is when the killer begins his gruesome revenge. The strange thing is that the first half of the film is composed with thin, needling suspense cues mostly, composed by Carl Zittrer. Tension building orchestral music that sets the mood for the second half with the prom party.

The killing starts and the disco music takes the stage with its trashy pulsating rhythm, syrupy strings and rubbery bass, so the violence feels indecently in rhythm! Paul Zaza and Carl Zittrer were behind the scores of superb horror movies like «Black Christmas» and «Murder by Decree», and they serve perfectly well this early post-«Halloween» slasher that leans hard on disco, drama, and teenage shame. You spend a lot of time with kids lying, covering up a childhood accident that turned fatal, and waiting for that to come back and cut their throats. When the killer finally shows up in the black outfit and ski mask, it’s almost more “revenge mystery” than pure maniac energy.

At the time of the movie’s release, there was only a soundtrack release in Japan by RCA on LP, including only the disco music and the songs and none of the orchestral score. This record was selling for 200$ or more for many years until the inevitable re-releases landed, by 1984 Publishing on LP and Perseverance on CD. The latter editions (both released in 2019) also contained the orchestral score for the first time. Of special interest is the 1984 Publishing release that came out in coloured vinyl and also included a condom in the package!

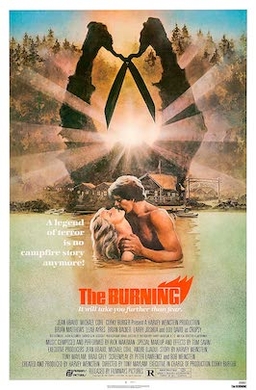

THE BURNING (1981)

«The Burning» is one of those early ’80s summer-camp

slashers that for many years was staying under the shade of «Friday the 13th

» as a straight rip-off. Time proved that it might well be a better

movie in almost all aspects. Plot-wise it’s simple: a caretaker gets burned in

a prank gone wrong, comes back scarred, and gets a bloody revenge upon the

youngsters he considers responsible for his disfigurement. You’ve heard that

setup before, and honestly, the movie isn’t pretending to be deep. What makes

it stand out is the attitude. Plot holes are deep but direction and

performances are superb for such kind of movie. The young actors– that later

some of them became big stars like Jason Alexander and Holly Hunter – are

amazing and perhaps the most likable and into the context characters that ever

appeared in a slasher movie. In essence, male and female characters, are

prototypes of slasher movie arcs – the bully, the sensitive, the funny, the

smart ass, the weirdo – but they are not presented like heads for chopping.

However, the plot is not less but nasty with them. The raft massacre sequence

is the movie’s calling card. Tom Savini’s effects are brutal, close-up, and

basically designed to make you wince, not cheer. The killer, Cropsy, doesn’t

feel supernatural or mythic. He feels like an angry adult tearing through kids.

Impact-wise, The Burning pushed the violence level higher for the genre. After

this, slashers had to compete on how outrageous the kills were, not just on who

the killer was. It definitely helped make genre bloodier, louder, and less shy.

Rick Wakeman’s score for The Burning is actually pretty minimal and cold. The music is structured in the vein of a John Carpenter soundtrack. You get pulsing low synth, icy sustained notes, tension that just hangs there. It helps sell Cropsy as this presence in the woods; not a mythic boogeyman like Michael Myers, more like a hunter lurking just out of frame. Even the memorable main theme is performed in low key mode.

The soundtrack album is a

different thing. Wakeman has stated that in order to prepare an album he could

not utilize the film music cuts. So, he arranged his music into big suites in

order to hear full cues and musical ideas that feel like proper tracks. It sounds

polished and very in contrast to how raw the movie is. The soundtrack is a

progressive studio album inspired by the film’s score. It was released in many

countries by the time the movie was released. Varese Sarabande released it in

the US with a striking cover art and it was also released in Japan (also

different album cover), Italy, France, Australia and U.K. (all had the same

cover art).

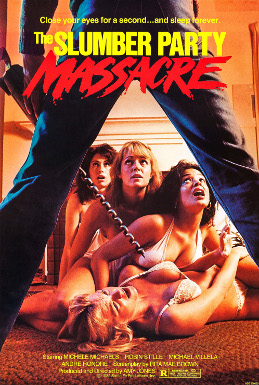

SLUMBER PARTY MASSACRE (1982)

Have you ever heard of a slasher

movie directed by a woman? I personally know no other case than Amy Holden

Jones who sat in director’s chair in «Slumber Party Massacre». A typical

sub-genre movie in the middle of peak slasher mania, when every other horror

movie was “A bunch of teenagers get killed with [insert household tool].” On

the surface, it totally plays the game: a group of high school girls, left

alone for the night, stalked by an escaped killer with a power drill…and a long

one!! Especially in the finale with the machete vs drill duel things escalate

to a cult level, including an unprecedented display of brave female resistance

against the raging killer.

There is information that the original script was meant as a parody of those slashers — it was supposed to be openly mocking the formula — but the producers basically said, “No, play it straight, that’ll sell better.” Production-wise, this thing was made for very little money by New World Pictures - which was Roger Corman’s operation - including fast shoots, low budget and lots of marketable elements (violence, nudity).

The score follows the same low budget path. Composed

by Ralph Jones, it sounds like it was made with the cheapest synthesizers

existing, reminded me of the sound of «X.T.R.O», another notoriously low

budget synth score of the era. In fact it’s this nervy little synth world that

keeps buzzing under everything. Nothing special actually. The surprising thing

is that the score was released on LP by a presumably home-based label named WEB

Records, that was also responsible for the release of a couple more soundtracks

among them Luciano Michelini’s «Screamers» (aka L’Isola Degli Uomini

Pesce - 1979). Contrary to other much more generously budgeted movies of the

era, this little film had a soundtrack that its scarcity increases as years

pass, reaching prices well over 100$. Death Waltz Records released a reissue in

2014 with a new cover art, but it didn’t have an impact to the original’s

collectible value.

SILENT NIGHT, DEADLY NIGHT (1984)

Santa Claus as a killer? «Silent

Night, Deadly Night» was not the first movie to present the gentle grandpa

(or at least its impersonation) as a killer force, but it was the first one

that did it with a blast! The film itself is a nasty little trauma story. a kid

named Billy watches his parents murdered by a guy in a Santa suit, grows up

abused in a Catholic orphanage, and eventually snaps at Christmas, putting on

the red suit and “punishing the naughty.” On its own, that wasn’t unique. What

was unique was how they sold it.

The distributor actually advertised the movie on TV during family programming in late November, using images of an axe-wielding Santa. Parents saw that, freaked out, and organized protests outside theatres. Moms’ groups called it sick, news shows ran outrage segments, and suddenly “killer Santa” wasn’t just in a midnight movie — it was on the evening news. The studio panicked and pulled the ads, then yanked the film from wide release completely. So instead of being a cheap seasonal slasher, it got branded “the movie too offensive to exist.” Very sad story indeed for a movie not bad at all, forty years after its problematic release in wide distribution over America.

Perry Botkin – who was nominated for an Oscar together with Barry Devorzon in 1971 for the wonderful song from «Best the Beasts and the Children» – was hired to compose the score. Unfortunately the pulsing synths, drones and atmospheres didn’t fit well to the Christmas backdrop of the film, which clearly needed something more clever and fitting. The surprise comes from the original songs Morgan Ames composed especially for the movie, as the producers didn’t choose to go with Christmas classic songs but composed entirely new tunes! To be honest, it seems to me that they work much better than the bland score.

After all the fuss with the

Killer Santa issue, a soundtrack release was out of the question during the

movie’s release, but in 2014 Death Waltz Records released a deluxe 2LP release

including both the Botkin score and Ames’ songs, in a superb release with an

insert with photos and text about the movie. Surprisingly there are three

different cd releases of the score, all double cd sets by Death Waltz, Howling

Wolf and Terror Vision.

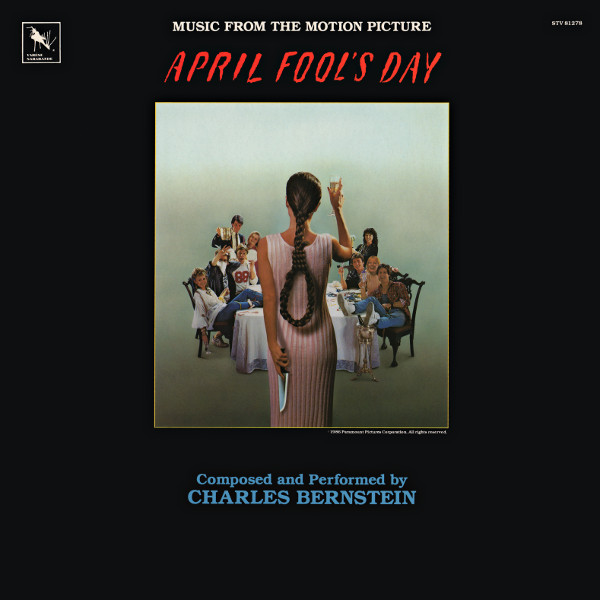

APRIL FOOL’S DAY

(1986)

«April

Fool’s Day» sits in a very specific moment:

the slasher boom is already bloated, the formula is predictable, audiences

think they know the rules and this movie basically messes with them for 90

minutes.

Setup sounds standard: a bunch of

rich college-age friends go to a remote island mansion for the weekend, and

they start getting killed off one by one in nasty, creative ways. Classic

body-count blueprint. Isolated location, suspects trapped, killer maybe among

them, standard slasher movie formula…

But here’s the difference, the movie is way more interested in playing with the audience than getting rid of the characters. It leans into mystery structure and fake-outs rather than sadistic murders. The characters are mostly annoying and upper-middle-class brats but they feel like real people with emotions and believable behaviour. Meanwhile, the story leans more toward a whodunit than a simple body-count slasher, because you’re always trying to figure out what’s really going on. Director Fred Walton («When a Stranger Calls» - 1979) knows how to stage suspense without screaming at you.

Charles Bernstein originally

wrote the music in a more traditional, orchestral style but what you mostly

hear in the finished movie is a mix of orchestra and synthesizers. Actually we

hear a superb opening credits theme and a suspenseful climax music performed by

an orchestra (with synthetic snippets) and the rest of the movie is scored with

a traditional slasher movie score heavy on suspenseful synthesizer stingers and

drones. Bernstein essentially brought back the musical style he’d used two

years earlier for «A

Nightmare on Elm Street». The

decision for the composer to repeat himself maintaining the ominous,

frightening tone of his biggest career success rather than “playing” with the

viewer the way the film itself does was spot on, and it effectively reinforced

the story’s overall deceptive tone.

The soundtrack album released at

the time of the movie’s release by Varese Sarabande label and contained the

synth score leaving out of the selections Bernstein’s orchestral work. Over the

years, the album gained a high collectible value as the majority of Varese Sarabande’s

genre soundtracks. The label reissued an expanded release a year ago including

in a double LP and CD the full orchestral and synth score Charles Bernstein

composed for the movie.

CHILD’S PLAY (1988)

«Child’s

Play» takes the most innocent object

in the room—a kid’s doll—and turns it into a street-level slasher with a

personality, riffing on Don Mancini’s ‘Blood Buddy’ concept born from the ’80s

toy craze and kid-targeted advertising, with a dying killer (Brad Dourif) using

voodoo to transfer his soul into a ‘Good Guy’ doll

Director Tom Holland, having a strong 80s horror resume writing «Psycho II» (1982) and directing «Fright Night» (1985), shoots from kid-height, keeps the camera low and mean, and saves full-body shots of Chucky until the tension’s wound tight. Kevin Yagher’s animatronics give the doll actual attitude—snarls, micro-expressions, quick bursts of movement—transforming a tiny cute doll to a ruthless killer. There’s also Brad Dourif’s voice that makes the doll’s presence even creepier and also the mother-son core, with superb performances by Catherine Hicks and Alex Vincent that gives the film a real the emotional spine, which most late-’80s slashers lacked.

«Child’s

Play» minted an instantly iconic

villain who wasn’t a silent mask but a motor-mouthed brand mascot from hell, helping

open the door to franchise-friendly high-concept horror.

Joe Renzetti scores «Child’s Play» like a bedtime story that curdles. Where

many ’80s slashers went for either Manfredini-style string stabs or Carpenter’s

minimalist synth pulse, Renzetti splits the difference: a nervy orchestral

backbone laced with toy-box colors—celesta, glockenspiel, music-box figures,

little clockwork rhythms. He takes the tones we associate with lullabies and

kids’ toys and twists them into a nightmarish, distinctly ’80s palette.

Milan records released the

soundtrack on LP and CD in 1988 in France. Later reissued on cd by La-la Land

in 2009 offering 20 minutes of more music. Waxwork reissued the Milan edition

on LP in 2019 in three different color variations.

Leave a Comment